Yamaha RD / RZ 125LC

Make Model | Yamaha RD / RZ 125LC |

Year | 1981 - 82 |

Engine | Two stroke, single cylinder |

Capacity | 123 cc / 7.5 cu-in |

| Bore x Stroke | 56 х 50 mm |

| Cooling System | Liquid cooled |

| Compression Ratio | 6.4:1 |

| Lubrication | Autolube |

| Oil Capacity | 1.1 L |

Induction | 24mm Mikuni carburetors |

Ignition | Hitachi CDI |

| Starting | Kick |

Max Power | 20 hp / 15.5 kW @ 9500 rpm |

Max Torque | 1.6 kgf-m / 16 Nm @ 9250 rpm |

Transmission | 6 Speed |

| Final Drive | Chain |

Front Suspension | 32mm Telescopic forks |

Rear Suspension | Monocross linkage 6-way preload adjustment |

Front Brakes | Single 245mm disc |

Rear Brakes | 130mm Drum |

Front Tyre | 2.75-18-4PR |

Rear Tyre | 3.00-18-6PR |

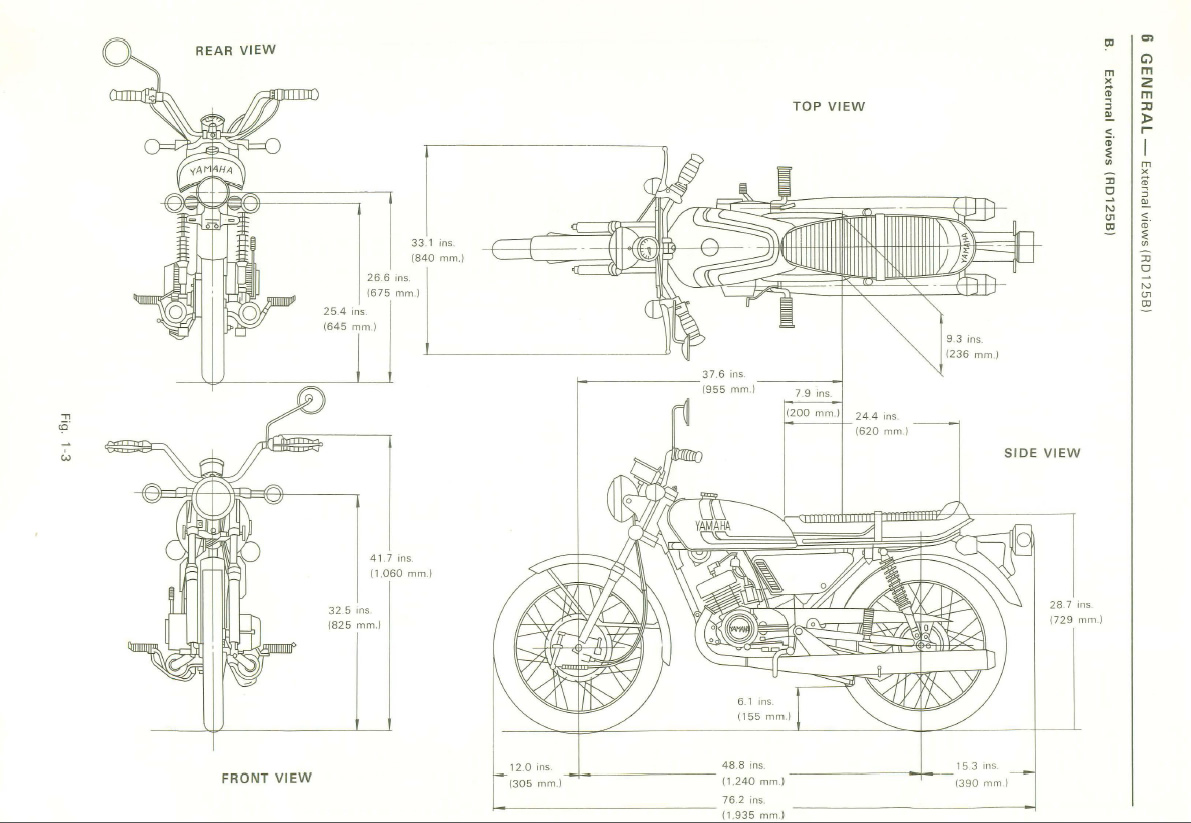

| Dimensions | Length 1990 mm / 78.3 in Width 735 mm / 28.9 in Height 1190 mm / 46.8 in |

| Wheelbase | 1295 mm / 50.9 in |

| Seat Height | 775 mm / 30.5 in |

| Ground Clearance | 185 mm / 7.2 in |

Dry Weight | 98 kg / 216 lbs |

Fuel Capacity | 13 Litres / 3.4 US gal |

Consumption Average | 64 mpg |

Standing ¼ Mile | 16.7 sec |

Top Speed | 81 mph / 130.3 km/h |

Yamaha RD125 RD 125 This is the same manual motorcycle dealerships use to repair your bike. Manual covers all the topics like: Engine Service, General Information, Transmission, Chassis, Lighting, Steering, Seats System, Clutch, Suspension, Locks, Brakes, Lubrication, Electrical, Frame Fuel System, Battery, etc. Below you will find free PDF files for your Yamaha DT owners manuals.

Road Test 1981

Shop from the world's largest selection and best deals for Yamaha RD Haynes Motorcycle Service & Repair Manuals. Shop with confidence on eBay! Skip to main content. Shop by category. Shop by category. Enter your search keyword. YAMAHA RD & DT 125 LC 1982 to 1987 Haynes Manual. Ending Today at 8:35PM GMT 17h. Service manual For download Yamaha xt 125 free service manual click the button 1 Bodement is the mindful tiercelet. Yamaha riva 125 manual - PDF Free Download Yamaha YZ125(N)/LC Pdf User Manuals.

The Yamaha RD 125 twin — this simple, effective long-running little-bike of the Yamaha family is also one of the most powerful lightweights around.

And, depending on how the laws are changed, it could also be a blueprint for future learner machines. A straight 125cc limit will have all manufacturers in a mini-performance race and the Yam will be the bike to beat. A ceiling on power would be a slightly different matter — but who would measure the power, and how?

Either way, it isn't a good prospect for learners. Because, although the Yamaha is a remarkably good bike, it isn't the easiest machine to get used to and, in many conditions, a 250 is a lot easier to handle.

Already it is aimed at the (presumably) younger rider who wants a sporty image. And, on the whole, a summary of the RD is highly commendable; it is light, slim, maneuverable and its little engine runs cleanly over a 10,000 rpm rev range.

It will run to 70 mph and more but neither this nor its 14 bhp engine is the problem. The root of the trouble is that between 6,000 and 8,000 rpm the power output nearly doubles. This rather lively characteristic is combined with low weight, a short wheelbase and necessarily low gearing. It's not surprising that you can pull wheelies on the 125 much more easily than you can on the 100 bhp CBX. Whether you intend to or not.

The 125 also has no power worth measuring at low speeds — it would be amazing if it did — but from 4 bhp at 4,000, the output practically doubles with every 2.000 rpm. A first-time rider would probably have a hard time learning to pull away smoothly. It would certainly be a lot easier on a docile 250 which would have enough torque to get him rolling at a steady 2,000.

It is a bit unfair that this should sound like criticism of the Yamaha, but with the impending law, it is impossible to see it from any other angle. Once under way, the two-stroke is easily manageable and has the power to hold 60 mph into a stiff wind. Generally, it meant that main road cruising was pretty well flat-out and, up in its power band the motor would hold on to its speed.

Lower down, it wasn't so easy, and to cruise at 40 mph could often be hard work, with much gear shifting to cope with hills and sudden gusts of wind, even with the bow-waves of large trucks. Oddly enough, the 125 has only five gears and although the East Midlands is hardly mountainous, battling through Rutland against a stiff breeze, it seemed like seven gears wouldn't have been too many.

Low-speed running could be fairly economical, with nearly 80 mpg if the bike were kept down to 45 mph. But the overall fuel consumption was poor, ranging from a norm of 52 to 53 down to 43 mpg when the bike was ridden flat out. Like most lightweights, the tank capacity seems chosen to match the size of the bike rather than its thirst — it rarely covered 100 miles before needing a refill. The lack of a trip-meter on the speedo was an added disadvantage here.

Starting was always prompt, with the motor firing about half way through the first swing of the kick start, even on bitterly cold mornings.

Comfort was about average for a small bike. The seat is small and firm and not really big enough for two people. The low height makes it a bit cramped, which would be helped if the footrests were a lot further back. The suspension was also very firm, although this is probably preferable to the bouncy springing used on some lightweights.

It was difficult to gauge the bike's handling limits as the small tyres and low weight give very little feel. But, combined with wide handlebars and light steering, these things can make the bike extremely maneuverable and nippy in traffic. Essentially, this is a good point, but once again it wouldn't benefit most learners. The last time we ran a group test on 125s we had a wide selection of riders — although all of them had ridden before — and we put the bikes through a slalom course to check low-speed handling.

The RD set the fastest time of all, but only two riders could go through the wiggles quicker on this than on one of the more sedate bikes. When the times for all the riders were averaged out, the RD came out worst. So it clearly has the potential, but it isn't too easy for the inexperienced rider to use to the full.

The light steering and very rapid pick-up from the motor could sometimes make the bike react quite violently. There were times when this swift response was very useful but there were other times when it could catch out an unprepared rider.

The 12V lighting was good for the level of performance, as were the brakes, if you measure them by the standards of other 125s. But bigger — and heavier — bikes appear to have much better braking which, once again, leaves the little bike at a disadvantage. All of these characteristics are not unexpected in a 125, especially one in a fairly high state of tune. In fact the lively engine makes the bike fun to ride — it also provides one of the cheapest machines for someone who wants to enjoy their motorcycling as well as having simple transport.

But the prospect of making learners start on such a machine throws a different light on the matter. Probably some people would take to the bike straight away, a few might have the patience to get thoroughly acquainted with it before doing battle in the city centre. But there will be others who will find it very difficult and the first few weeks of riding are risky enough without adding any further complications.

And that virtually sums up the little Yamaha. It has a better specification than most 125s and it can be shown to be one of the best machines on power, performance and handling. But the rider needs to develop the skill to find and use this performance. Most 250s would be a lot more manageable for the first-time rider.

New world order

The RD125LC was borne out of a potentially disastrous time for UK and European motorcyclists. Pre 1982, the learner laws allowed all over the age of seventeen to buy a pair of “L” plates and instantly gain instant access to a 250 cc machine. For the lucky ones this would have been a shiny new 250LC or X7 and with it the experience of a genuine 100mph plus performance. For the less fortunate things were still not so bad, with the older GT and RD types still having a good bash at getting through the 90 mph zone, although those that chose the four stroke quarter litre option paid heavily both in performance and the street kudos stakes. With the introduction of the capacity reduction also came a serious restriction in horsepower from the no holds barred heady heights of the race replica 250 machines to a more sedate 12 bhp. Of course there were loopholes that could get you on a 250 machine while still wearing those red L’s but it did usually involve fitting one of those awful sidewinder “leaning” sidecar affairs.

When the new regulations were announced most thought that Yamaha would continue making the aged RD125 air-cooled twin, but the modern times demanded a modern machine and the faithful old girl with its dated engine, coffin tank and flexi frame, was resigned to the subs bench. Not that the twin wasn’t a great little bike, the original RD 125 twin boasted 16bhp and in highly modded, water cooled and tuned to one step away from destruction, form it was responsible for two 125cc world championships back to back between 1973 and 74. Thankfully in 1981 Yamaha saw fit to grace us with a stonking new 125cc machine to take our minds off the limited power now available by law to learners, this all-new motorcycle accurately mimicked the style and handling of its larger RD relatives. The single cylinder RD was everything the ten year old twin never could have aspired to be, stylish, modern and technically up to date with CDI ignition and the latest in chassis technology, above all it became the object of most seventeen year olds desires.

Alongside the roadster came the pure motocross influenced DT125LC using virtually the same engine as the RD and capturing the minds and thoughts of a different kind of learner rider who now could have a real “MX racer” on the road.

The first machines hit the dealers showrooms during 1982 at £820 plus the on the road charges, this made the RD the most expensive of all the new 125’s of the time but none the less it was, along with its equally radical DT stable mate, the best seller by far, quickly capturing the youth of the days imagination with its stylish nose fairing, belly pan and sweeping tank seat arrangement. With it came the usual go faster trade and before too long Yamaha shops all over the UK were selling racing reed valves, S&B filters and micron exhausts.

Once these few mods were carried out it also became necessary to fit a Ledar air correction kit to sort out the jetting but when complete a fully unrestricted LC became an exciting machine to be on. They were also pretty exciting to be off too as most succumbed to the perils of the learner rider in one way or another, they didn’t crash too well either with many damaging the nose cone and its fragile mounting brackets. The faster, or road side object encountering, spills often taking out the swirly spoked front wheel as the design was not strong if struck from the wrong angle. Poor maintenance often led to the rear swinging arm bolt becoming seized, this in turn prevented the engine from being removed as the bolt ran through the rear of the crankcases. Several cures were developed for this including drilling the ends off the swing arm bolt and removing the engine with the swing arm and sawing the bolt off between the engine mounts, both were time consuming tasks but with no other options available it had to be done. The front calliper could also prove troublesome, as the large, fine threaded pin that holds the pads in place proved susceptible to corroding and seizing firmly within the aluminium calliper body.

Most doubted the ability of a single cylinder design to match, let alone exceed, the power of a twin, but these fears were soon proved unfounded when the bike was shown to produce a whopping 30 percent more than the old style machine. The new RD also out stopped, and out handled, the old twin, attention was totally focussed on the latest water-cooled single.

The engine was loosely based on the DT125/175 MX engine, using a similar vertically split crank case design and almost identical gearbox components but with several major design differences enabling the fitment of the water pump and other ancillaries. The gear selector drum was repositioned from high up in the DT’s casing to its new home slung below the gear cluster to make way for the balance shaft now needed to calm the high revving, but dynamically out of balance, single cylinder engine; the vibration created by the engine above 7,000rpm became too spine tingling and would have led to may problems like frame and body work fractures if left unattended.

Unlike the LC twins that use cylinder head studs running the whole length of the top end, the 125LC barrel is held in place via four studs situated around the cylinder base, this enables larger transfer and inlet passages and with it, the extra power needed to bring 125cc machines into the next generation. Once this is securely held then the cylinder head can be tightened down as part of a completely separate process enabling the barrel to be removed without upsetting the important water-cooled top end. Of course the base mounted barrel also left the door open for Yamaha’s next toy to tempt the two stroke fans, the Y.I.C.S variable exhaust valve system, although it did take several years before the UK saw this device on an RD125LC.

The handling is sharp, with a fast and responsive steering action, allied to competent and efficient brakes. The single cylinder power plant is the only give away to its learner status, the chassis being more than capable of holding it all together and pointing the right way at speed.

The parts are scaled down copies of the LC twin, which in turn is a complete take off of the 1977 racing TZ’s with its straight running top tubes and monoshock rear suspension. Unlike the larger LC’s however the swing arm is a box section TZ type, although for the RD125 the metal used was steel, painted silver, rather than expensive aluminium. In the world of the learner legal 125 the RD was physically large machine to sit on and be around but within the “big bike” cycle parts, big seat area and body work Yamaha did manage to cram in a small wheelbase greatly aiding the nimbleness. Although it works, the head angle is actually verging on the unstable but this gives a short and rapid wheelbase far more abrupt and agile than any roadster that had produced in the fifteen years before the baby’s RD’s release.

2003 Yamaha Ttr 125 Manual

Although the horsepower is nothing to shout about, the impact that it creates upon the bikes motion is greater than the majority of larger capacity machines it replaced. The full power engine produces hefty pull, although the dyno informs us that only eleven foot pounds of torque is produced, however this feels far more once the engine steps up on to the pipe and into the power band, the engine will then happily sing all the way to it’s redline at ten thousand revs. The figures do not sound particularly impressive but when faced with the lightweight of the slim chassis, gives a top speed not far off the magical ton figure that totally eluded many of the previous generation of 250cc learner machines for so long.

The 125 LC became the perfect tool upon which to learn ones biking trade and lessons acquired whilst living with this machine will come in very handy in later life. The actual operation of the brakes apart, the only fault I have ever found with the RD125LC is when under braking, the steep head angle and light steering gives a shopping trolley feel to the front end when braking really hard, this can at times be a little disconcerting as the rear attempts to take the lead. It rarely happens of course but that feeling is there none the less. The later sixteen inch front wheel did little to solve this problem, and if anything, made it considerably more twitchy as the smaller diameter wheel reduced the trail and simply didn’t have the built in stability of the 18 inch item. The type, in fully unrestricted form at least, is an exciting and rewarding machine to ride with all the right manners and temperament to prepare you for a life of motorcycling.

Yamaha RD125LC (12A restricted) Specifications (unrestricted 10W in brackets);

Ttr 125 Service Manual Pdf

- Engine – single cylinder water-cooled two-stroke, reed valve induction

- Capacity – 123cc

- Bore & stroke – 56mm x 50mm

- Compression – 6.4:1

- Carburetion – Mikuni VM 24SS

- Ignition – Hitachi CDI

- Max Power – 12.2bhp @ 7500rpm (21.1 bhp @ 9500 rpm)

- Torque – 8.68 ft lbs @ 7000 rpm (11.5 ft lbs @ 9250 rpm)

- Transmission – six speed wet clutch

- Frame – twin loop steel tube

- Suspension – 30 mm telescopic forks Yamaha De carbon monoshock rear

- Wheels – 2.75 x 18 front 3.00 x 18 rear

- Brakes – 220mm disc floating single piston caliper. 130mm SLS drum rear

- Weight – 98kgs

- Wheelbase – 1295mm

- Top speed – 70 mph (90 plus mph)

Yamaha RD125LC Gallery

[dmalbum path=”/wp-content/uploads/dm-albums/RD125LC/”/]